By Anna May

My grandad has become obsessed with cleaning his hands. Every half an hour he hobbles into the kitchen, holding on to the door frame, the radiator, the backs of chairs. Whatever to steady himself.

“You okay Grandad?” I ask.

“Just washing my hands” he says.

Apparently you can recycle old pill packets. They have a whole draw of little empty trays with the days of the week popped out and empty, waiting for their trip to the tip.

In the draw above there are dozens of cleaned out yoghurt pots and ice cream tubs and a strange collection of felt owls.

My grandad shuffles round on his frame, unsure where he is trying to go. One moment he asks us what time tea will be, and the next he sobs. I can’t bare it. My lovely Tom. Oh darling. My lovely boy.

His heart is breaking so loudly I can feel it in my own chest.

The neighbour brings us a tray of apple crumble and we eat it for lunch. Not because we are hungry, but for something to do. My granny complains there’s not enough apple, but all I taste is love.

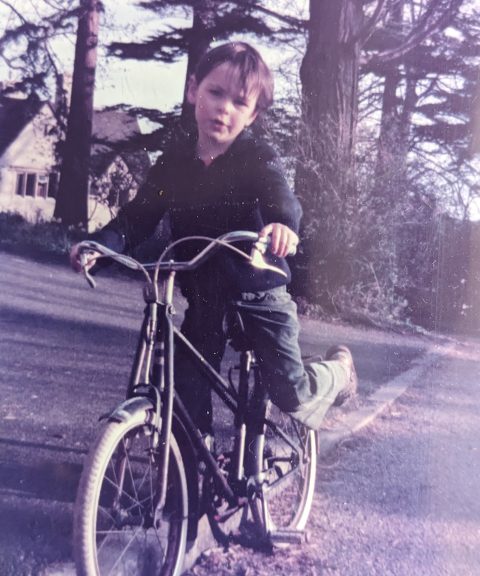

We sit at the table quietly, talking logistics. Your driving licence is in a plastic wallet next to my plate, with a utility bill and a bank statement. Seeing your picture makes me cry. You look so serious and have a full head of hair.

Some of your birthday cards have come through the post. People organised enough to send them a week before, who had no way of knowing you’d be gone by the time it came around. My grandad reads them again and again.

At one point he looks up and tells my granny he loves her. She doesn’t know what to say and asks him if he has his hearing aid in. We are trying to learn how to speak loudly without shouting. How to be soft.

It’s hard to believe it’s only been two days. Or three. I’m not sure whether to count the early hours in the hospice. Time has taken on a fuzzy grey quality where twos and threes become one and none means nothing at all.

My granny stays in her room upstairs, listening to the radio. A candle burns on her bedside table. Every now and then she gets a call from one of her friends. I hear her saying that she hopes you enjoyed your life.

I could tell when you’d died by the way my mum was speaking on the phone when I came into the room. She put out her hand to me and kept talking. Practical stuff. Where the body would go next and which numbers we needed to ring.

When she’d finished, she put the phone on the table very slowly and we sat together in silence. We are both wondering if we should have been there. Or if you waited ‘til it was quiet, and you had the privacy.

You always liked solitude. I just I hope you didn’t feel alone.

Mostly I am fine. Mostly I am separate from it. I am preparing food and washing up and putting out the medication for the next meal. I am checking my emails and explaining to work that I won’t be back in the office tomorrow.

Mostly I cry when someone asks me if I’m okay.

My grandad is standing up again, as if to go somewhere. Or do something. It isn’t right, for your son to die before you do.

Oh darling. My Tom. My lovely boy.